Canton POS

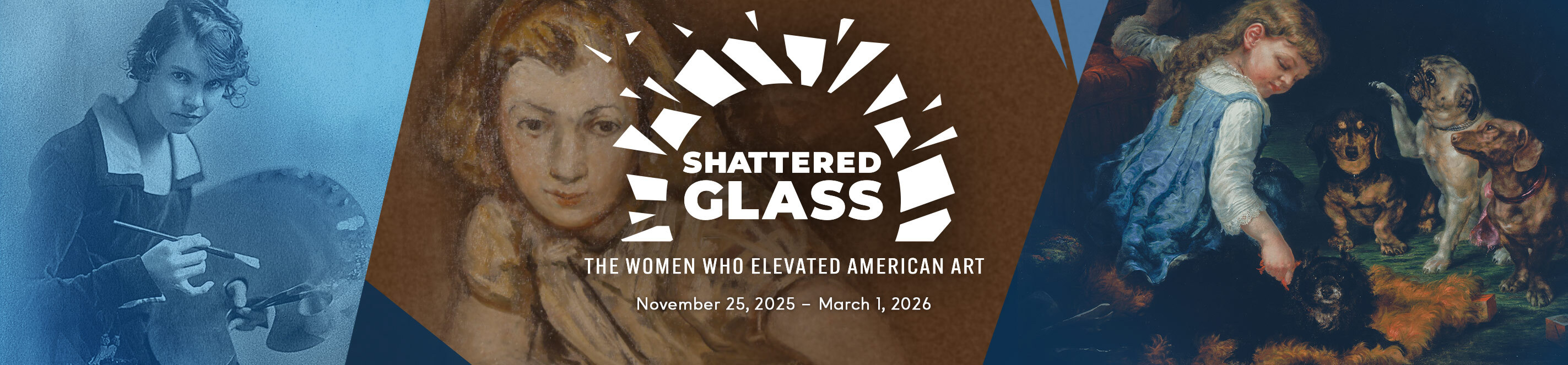

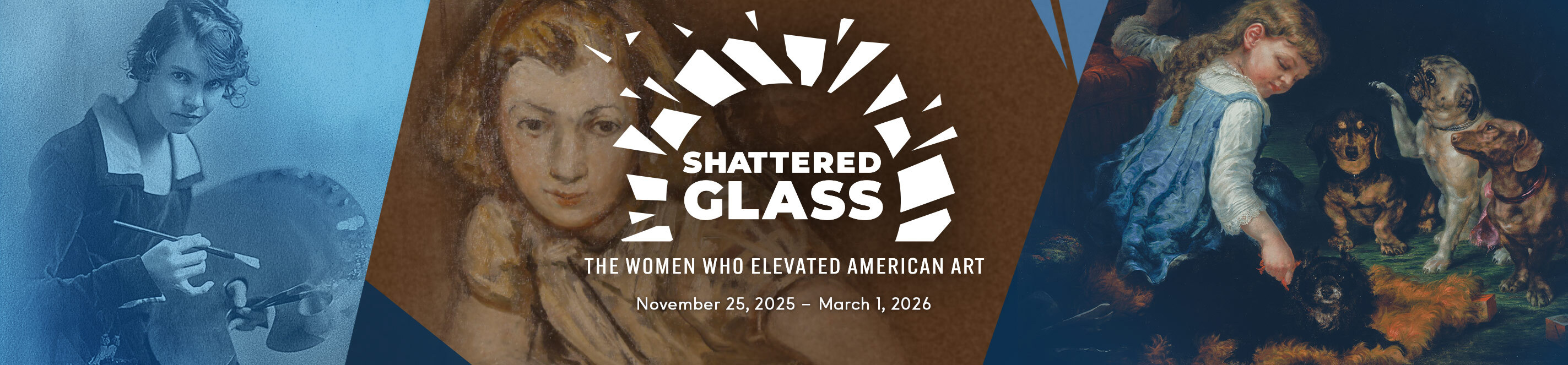

Shattered Glass: The Women Who Elevated American Art (November 25, 2025 - March 1, 2026)

Shattered Glass refers to breaking the "glass ceiling," a metaphor for the invisible barriers that prevent qualified people from advancing in their careers, especially underrepresented groups, including women. Shattered Glass is the first original exhibit held at the Canton Museum of Art to highlight only female artists and their heavily ignored contributions. Particular focus is given to those women who faced adversity due to not only their gender, but also race, sexuality, economic status, family, and life challenges. A sub-theme within the exhibition will focus on the women who created and exhibited their work under a male pseudonym, some of whom only revealed the truth in recent years or upon their death.

From the outset, women artists faced criticism simply because of their gender, a hurdle that proved difficult to overcome. Quotes abound from men voicing their dismissal of women’s artistic skill. In 1910 an Art News article proclaimed it was an “undoubted truth” that “...there are few women who can paint or model as strongly or successfully as men” in reaction to a statement from Dr. John Jenks Thomas that “Not one woman in a hundred has a true artistic sense." Similarly, Arthur Schopenhauer, known as “the artist’s philosopher,” expressed, “Women have proved incapable of a single truly great, genuine and original achievement in art, or indeed of creating anything at all of lasting value.”

Barred from an academic education until the 19th century and from most professions, middle-class women in America were intentionally confined to the home by societal norms to fulfill their expected domestic responsibilities. Because of these expectations, the ages from 18 to 35, critical for the development of most artists, were rarely available to most women for training and development in the arts. Any art instruction that they were able to obtain was solely intended to train them in culture and sophistication, not to prepare them for a career. Additionally, women were almost exclusively omitted from any art publications until the 1970s when the feminist movement gained traction along with the essay written by Linda Nochlin titled “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”.

It can be easy to assume that the sexism faced by nineteenth century women artists has disappeared, when in reality, those barriers closely resemble the ones faced by women artists today. Due to overwhelming societal pressures, gallery sales and prices of the work of female artists still lag behind those of male artists. According to the National Endowment for the Arts, on average, female visual artists earn 74¢ for every dollar made by male artists, causing women to receive lower returns from investing their energies into art. A study published in 2019 found that in the collections of eighteen major US art museums, 87% of the artworks were made by men, and women artists only represented 30% of the artists represented by galleries.

Many of the artists in Shattered Glass have fought for their right to create art alongside their male contemporaries and while doing so, revolutionized their field. While some were more reserved in their approach, others were not. Shattered Glass aims to shine a light on the remarkable artists so often excluded from history books, and start a conversation about their enormous contributions.

Judy Chicago made significant contributions to the feminist art movement, founding the first feminist art program in the United States, and creating work that brought attention to the role of women in history.

Judy Chicago made significant contributions to the feminist art movement, founding the first feminist art program in the United States, and creating work that brought attention to the role of women in history.

This test plate was created for Judy Chicago's Dinner Party installation - a table with 39 place settings commemorating an important woman from history and an important icon of 1970s feminist art. This particular plate test plate commemorates Sojourner Truth, abolitionist and suffragist. The raised fist on the right side of the plate is a reference to Truth's speech at the Women's Rights Convention in 1851.

This test plate was created for Judy Chicago's Dinner Party installation - a table with 39 place settings commemorating an important woman from history and an important icon of 1970s feminist art. This particular plate test plate commemorates Sojourner Truth, abolitionist and suffragist. The raised fist on the right side of the plate is a reference to Truth's speech at the Women's Rights Convention in 1851.

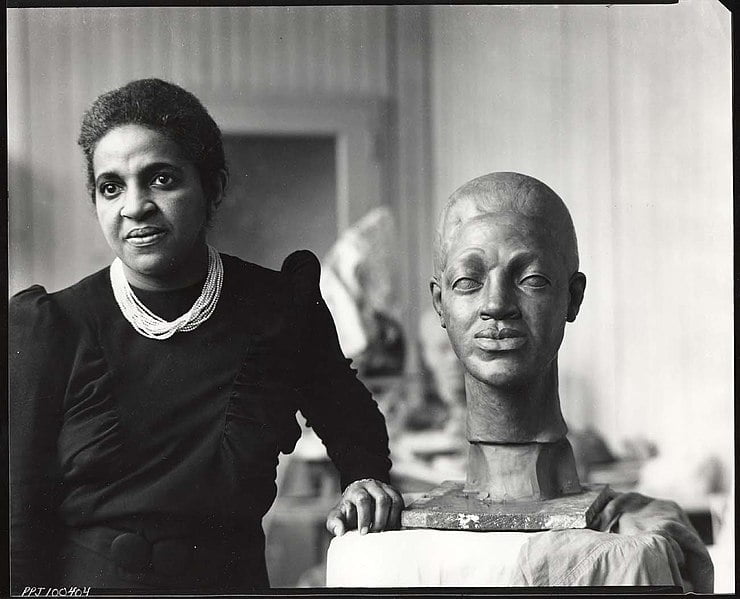

Selma Burke was one of the most distinguished African American sculptors of the 20th century, and one of the first African American women to join the U.S. Navy during World War II. She created the relief portrait of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, which was the model for his image on the dime, though credit was given to a man.

Created during the devastation of the Vietnam War and racial unrest throughout the United States, Peace shows a variation on the mother and child theme where the infant has been replaced by a dove symbolizing peace.

Alice Schille received recognition as the foremost watercolorist in the United States and had a successful artistic career, yet was written out of art history.

Guatemalan Rooftops demonstrates Schille's technique as one of the first American artists to use modernism in their work, and showcases her skill with watercolor as well as her travels, which women were discouraged from.

Audrey Flack was one of the first photorealist painters and one of the first to base her paintings on photographs. Her work challenged traditional perceptions of femininity through everyday objects.

Marilyn is one work from Flack's Vanitas series inspired by the still lifes of 17th century Flemish painters that were full of symbolism. Flack created the series to "encourage the viewer to think about the meaning and purpose of life." With hyperrealistic detail, Marilyn features an abundance of symbolism representing Marilyn Monroe's life, and how we viewed her.

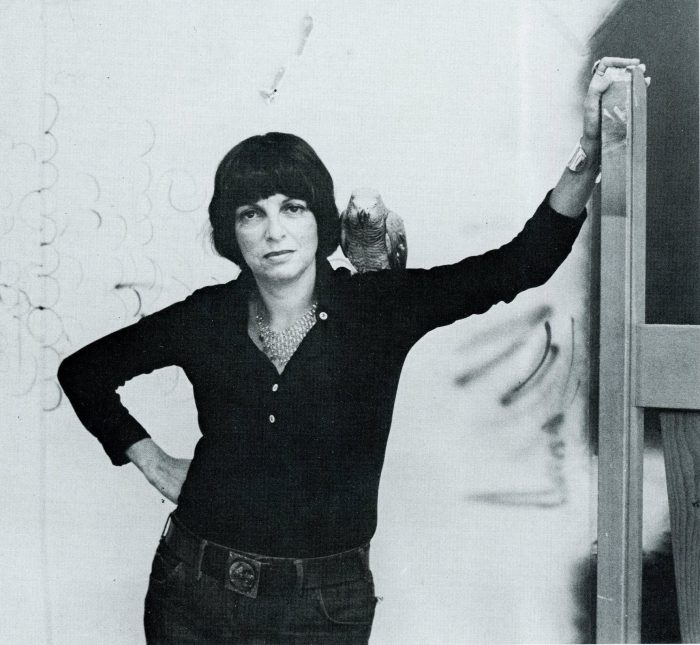

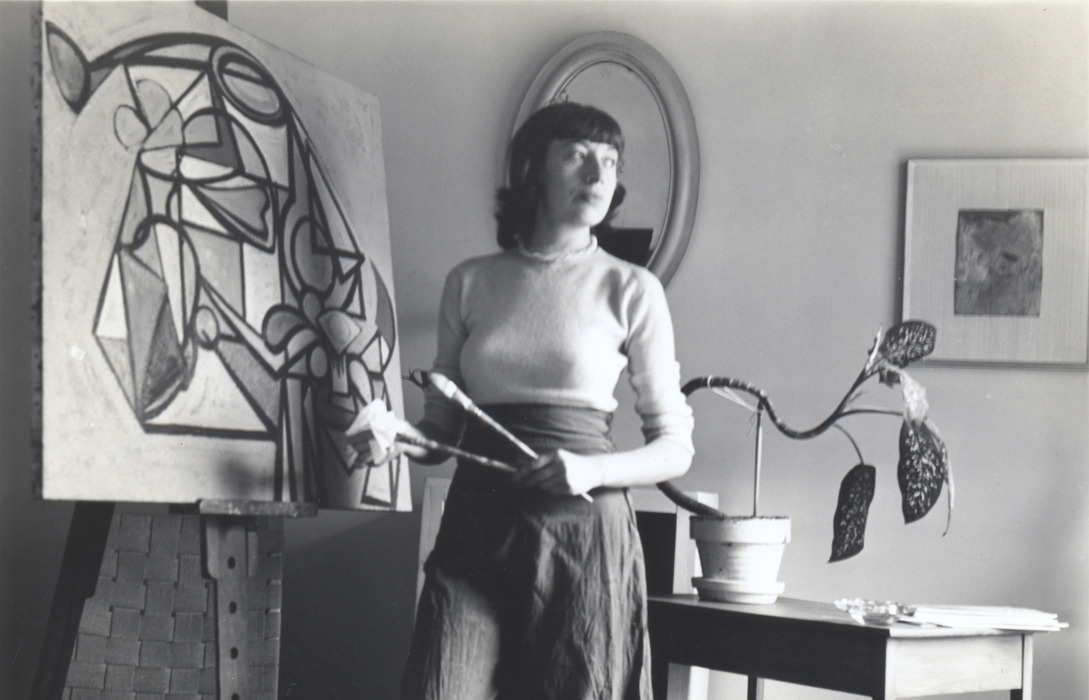

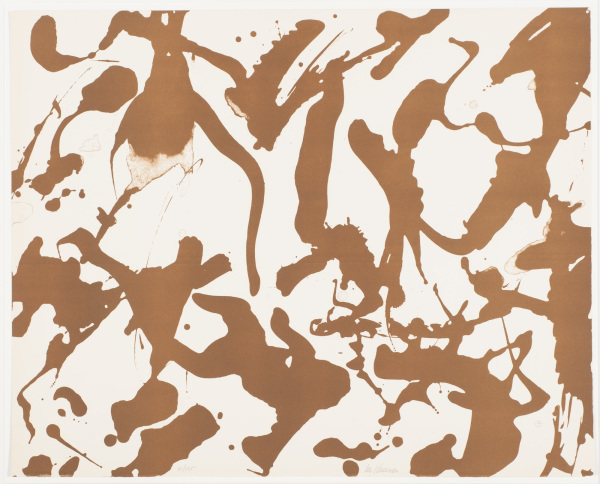

Lee Krasner was a key figure and pioneer of Abstract Expressionism whose work influenced husband Jackson Pollock's drip paintings and who advanced Pollock's career by introducing him to influential artists and critics.

Lee Krasner was a key figure and pioneer of Abstract Expressionism whose work influenced husband Jackson Pollock's drip paintings and who advanced Pollock's career by introducing him to influential artists and critics.

Krasner's work demonstrates her all-over technique that inspired Jackson Pollock, as well as her bold experimentation and contributions to Abstract Expressionism that were overshadowed by her male counterparts.

Maija Grotell was a pioneering figure in elevating ceramics to fine art, and one of the most influential potters working during the 1930s and 1940s. She revolutionized ceramics in the United States with a new form of wheel throwing and is often referred to as the "mother of American ceramics." She also reestablished Cranbrook as a premier clay education program.

Maija Grotell was a pioneering figure in elevating ceramics to fine art, and one of the most influential potters working during the 1930s and 1940s. She revolutionized ceramics in the United States with a new form of wheel throwing and is often referred to as the "mother of American ceramics." She also reestablished Cranbrook as a premier clay education program.

Grotell was an innovater in ceramic glazes and designs, techniques she developed which revolutioned the ceramics world. Her intense blue-green glaze was called "Grotell blue" and one of her colored glaze formulas opened the door to architectural uses of colored bricks in architecture.

Grotell was an innovater in ceramic glazes and designs, techniques she developed which revolutioned the ceramics world. Her intense blue-green glaze was called "Grotell blue" and one of her colored glaze formulas opened the door to architectural uses of colored bricks in architecture.

Other highlights include work by: Elaine de Kooning, Georgia O'Keeffe, Elizabeth Nourse, Mary Cassatt, Jenny Holzer, Audrey Flack, Diane Arbus, Dorothea Lange, Kara Walker, The Guerilla Girls, Beatrice Wood, Ana Mendieta, and Wendy Red Star, among many others.

The artworks in Shattered Glass come from the Canton Museum of Art's own Collection, in addition to loans from museums nationwide and private collectors. Artworks are in a variety of mediums, from oil paintings to ceramics and film, for a total of around 100 works by glass-shattering artists.

This exhibition has been made possible in part by:

Visit Canton | ArtsInStark

The Timken Foundation of Canton

Ohio Arts Council | Ohio Humanities

Stark Community Foundation:

Canton Museum of Art Exhibition Endowment

The Paparella Family Foundation

Canton Museum of Art Volunteer Angels

Images from top to bottom:

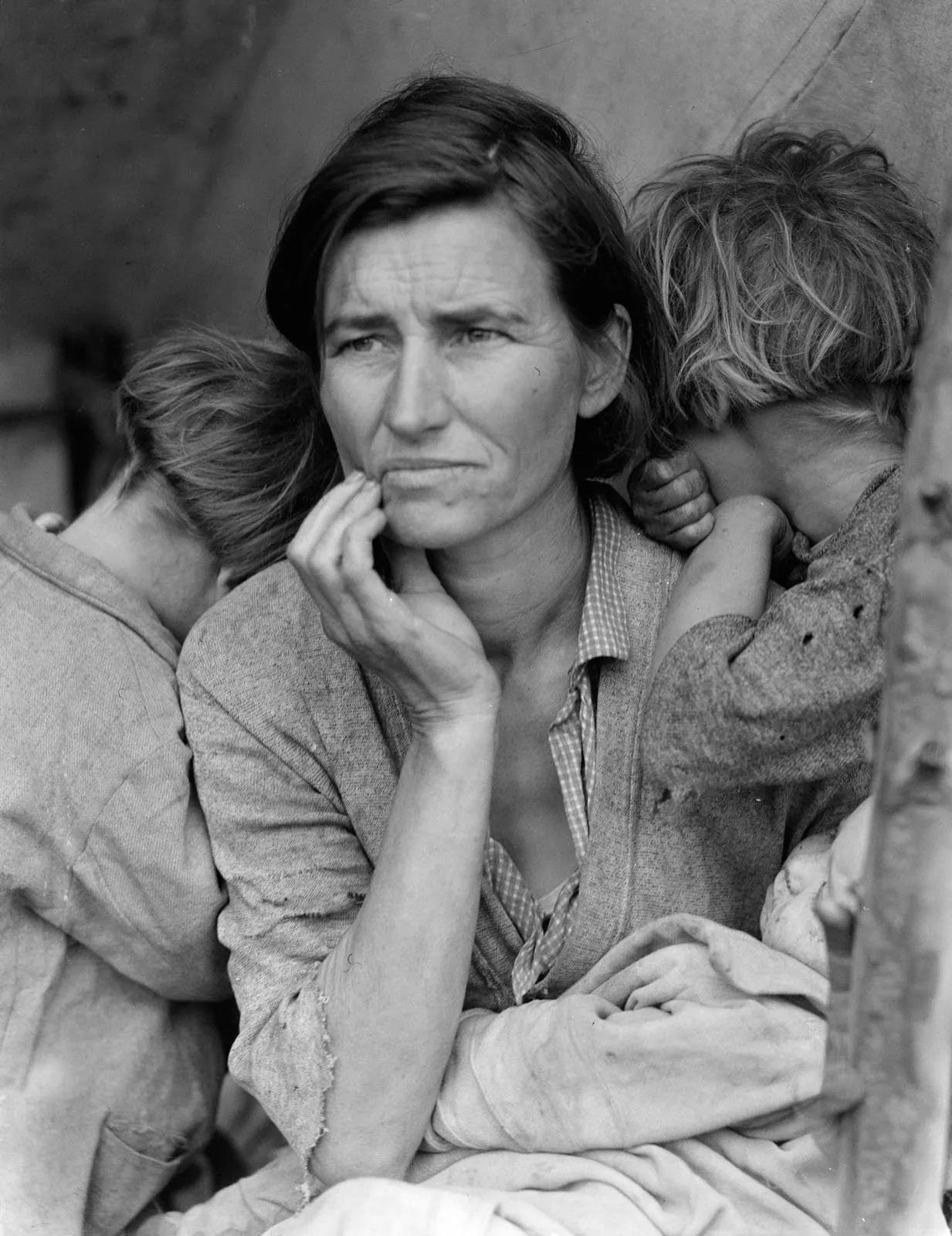

Migrant Mother, 1936. Dorothea Lange (1895 - 1965). Gelatin silver print, 19 7/8 x 16 in. Loan courtesy of Kalamazoo Institute of Arts.

Winter from the Four Seasons series, 2006. Wendy Red Star (b. 1981). Digital inkjet print, 35 1/2 x 37 in. Loan courtesy of St. Louis Art Museum.

Sous les arbres (Under the Trees), 1902. Elizabeth Nourse (1859 - 1938). Oil on canvas, 26 x 27 7/8 in. Loan courtesy of Sheldon Museum of Art.

The Dogged Class, 1885. Lilly Martin Spencer (1822 - 1902). Oil on canvas, 36 x 48 3/16 in. Loan courtesy of Cincinnati Art Museum.

Untitled Film Still #3, 1977. Cindy Sherman (b. 1954). Gelatin silver print, 30 x 40 in. Loan courtesy of Marlene and David Persky.

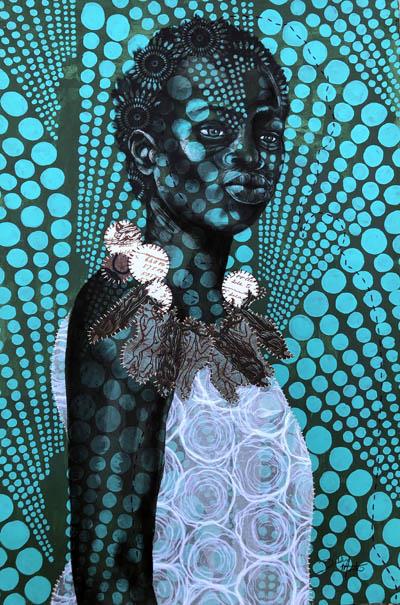

Carry this in Remembrance of Me, 2019. Delita Martin (b. 1972). Acrylic, charcoal, lithography, relief printing, decorative paper, and hand stitching, 51 1/8 x 34 7/8 in. Loan courtesy of Muscarelle Museum of Art.

Sojourner Truth Test Plate #2 from the Dinner Party, c. 1978. Judy Chicago (b. 1939). Porcelain, overglaze enamels, copper alloy, and plexiglass, 1 3/8 x 14 in. Loan courtesy of Brooklyn Museum.

Peace, n.d. Selma Burke (1900 - 1995). Bronze, 18 x 9 x 9 in. Loan courtesy of Spelman College Museum of Fine Art.

Guatemalan Rooftops, c. 1930. Alice Schille (1869 - 1955). Watercolor on paper, 17 1/2 x 20 1/2 in. Permanent Collection of the Canton Museum of Art, Gift of James M. Keny.

Marilyn from the Vanitas series, 1977. Audrey Flack (1931 - 2024). Oil over acrylic on canvas, 96 x 96 in. Loan courtesy of University of Arizona Museum of Art.

Untitled, 1970. Lee Krasner (1908 - 1984). Lithograph, 29 7/8 x 25 15/16 in. Loan courtesy of Cincinnati Art Museum.

Untitled, n.d. Maija Grotell (1899 - 1973). Electric-fired clay, 10 1/4 x 8 x 8 in. Permanent Collection of the Canton Museum of Art.

Acme Laundry in Cincinnati, c. 1910. Augusta Caroline Lord (1860 - 1927). Oil on canvas. Loan courtesy of Ohio History Connection.